Introduction: Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock, we all know there is something wrong with our healthcare system. Atul Gawande, Elisabeth Rosenthal, and others have eloquently laid it out: we pay too much, receive more care than is wise, and end up less healthy than we should be. In the midst of a national dialogue in which a partisan divide straddles almost every topic, there is remarkable consensus on the broad nature of what is wrong with healthcare in America. We agree on the problem, what is less clear is what the solution should look like. Some argue government and reforming regulation will do the trick, others that the solution will come from the insurance sector (as the sector through which all the money and much of the data in healthcare flows). I would argue that at the end of the day, care delivery is the beating heart of healthcare. It’s possible (but not wise) to have healthcare without regulation, and without insurance (modern health insurance is a relatively recent innovation of the early 20th century), but there is no such thing as healthcare without a caregiver giving care to a patient. The care delivery space represents over 60% of the $3.5BN+ healthcare industry, and if we are to truly address the shortfalls of US healthcare, the care delivery system of the 21st century will have to look a lot different than the system of the 20th century.

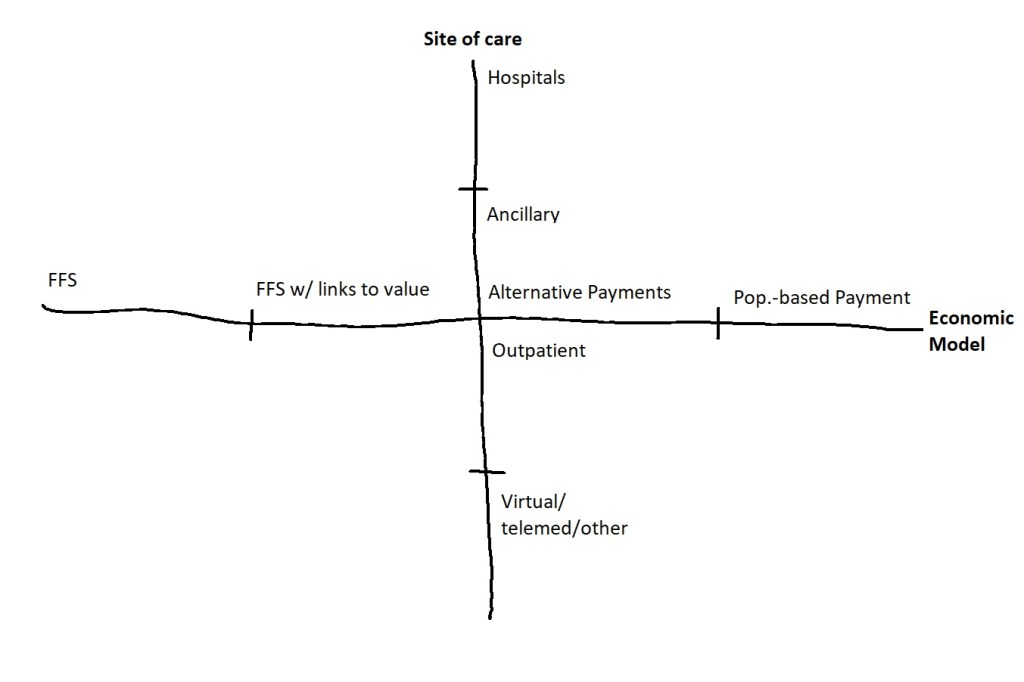

It’s hard to know where we’re going without knowing where we are today. I wanted to paint a mental picture for myself of the care delivery landscape, and I ended up with 12 archetypes of the major types of care delivery organizations (CDO’s) in America. I also wanted to use a simple framework to think about key differences between these organizations, and the role they each play in the ecosystem. To that end, I landed on two dimensions that I believe are the most relevant lens to think about change in this space: 1 – site of care, and 2 – the underlying economic model of CDO’s.

Obligatory grain of salt: This was an informal mental exercise I undertook to clarify my own mental picture of the industry. I do not lay the slightest claim to be authoritative or exhaustive. If you find mis-characterizations, please know that they stem from ignorance and not any intention to distort, and I would be grateful if you pointed them out. As for the pontification on where the winds are blowing, I am no soothsayer, and my views here are only educated guesses formed from my very incomplete understanding. These views are purely my own and do not represent those of my employer (Oak Street Health).

Site of Care: The hospital has become the undisputed locus of where care is provided in America. Not only do essential services like inpatient surgeries and acute emergent care take place exclusively in hospitals, but due to a set of curious financial incentives, more and more outpatient services have moved from your small doctor’s clinic down the street to the sprawling medical center downtown. Furthermore, hospitals and the health systems that own and run them have grown bigger, acquired more assets, and have become in general the most dominant organizations in care delivery. Historically, the vast majority of American physicians were independent; that is – they were their own employers. In 1983, this represented over 75% of all doctors, but in 2018, employed physicians (usually employed by hospital systems) outnumbered physicians in private practice for the first time.

Despite the fact that the hospital is currently the sun around which other CDO’s orbit, we seem to be due for something of a reversal. There is a broad consensus that hospitals may not be the best setting to deliver all (or even most) of care, and that more and more care should and will shift towards outpatient and alternative settings. If the hospital is the central hub today, alternative sites of service that tend to be less resource-intensive and designed for lower acuity care are on the rise. To visualize the trend, I’ve drawn a spectrum of sites of care below, ranging from inpatient hospitals to ever more “peripheral” sites in rough descending order of capital-intensity and care acuity, with the more novel and innovative modes of care like virtual care at the outermost periphery. I’ve placed ancillary on top of outpatient due to the relative higher capital intensity of facilities like SNF’s, LTAC’s, and hospice care, and the close de facto relationship of post-acute facilities as downstream discharge referral sites for inpatient visits. However, one can argue that these two layers should be flipped.

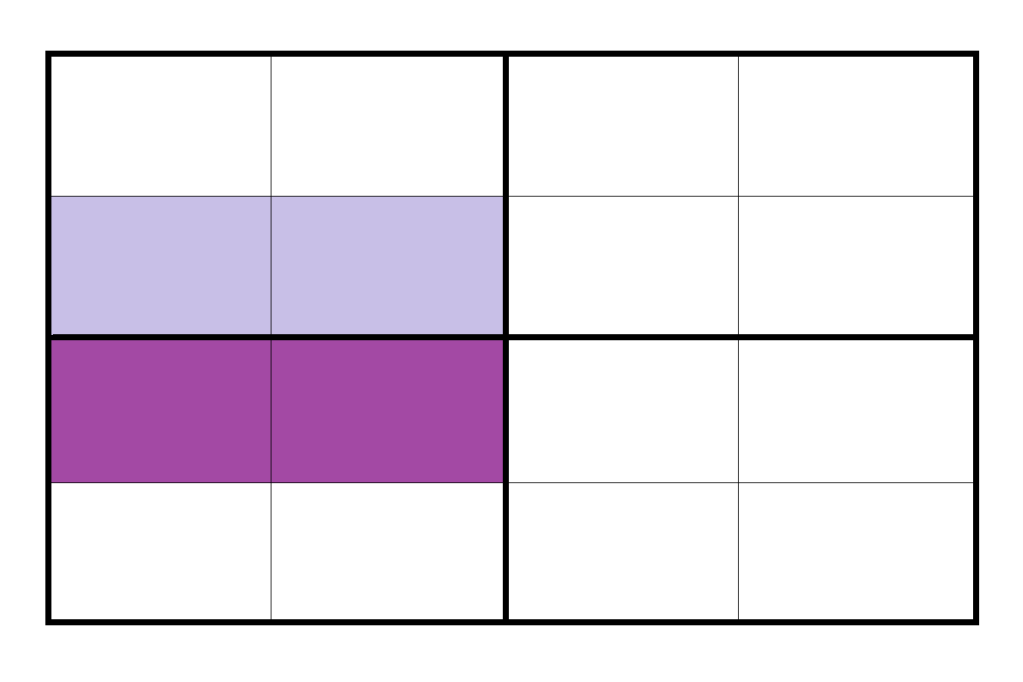

Economic model: In addition to the shift in sites of care, another emerging sea change to care delivery has been the emergence of alternative economic models for CDO’s. In contrast to the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) model which incentivizes higher volume of services, a wide variety of new models that links financial incentives to quality of care and patient outcomes are seeing rising adoption. The term “value-based care” has been used as an umbrella term for these new models, which range from quality incentives that function as a minor departure to the FFS model, to completely overhauled models like providers that take on full risk through globally capitated payments. The Health Care Payment Learning & Action Network (HCP LAN) provides a useful framework below to think about the spectrum of economic models ranging from traditional FFS on the left to the most radically different value-based models on the right.

Source: HCP LAN 2017 APM Framework Whitepaper

The framework: With respect to site of care, the lion’s share of care (a little over half on $ terms) is provided in a hospital setting, reflecting the dominance of hospitals as the central hub (NHE report 2018). Approximately 1/6th of care occurs in ancillary settings (our second ring of mostly nursing care, long-term care, and residential services), and outpatient services comprises about 1/3rd of care. The remaining segment of virtual care and telemedicine is historically a nascent marginal share of the total, but the recent Coronavirus pandemic and the following public response has shifted much of traditional in-person care to telehealth, triggering a growth in telehealth activity by orders of magnitude.

With respect to economic model, the center of gravity total is still closer to FFS than to fully-realized value-based care. According to the HCP LAN 2018 Report, categories 1 and 2 (FFS and FFS with quality bonuses) make up about 40% and 25% of total payments, while more the progressive value-based models, category 3 (alternative payments) and 4 (“population-based payment”) make up the minority with about 30% and 5% of total payments.

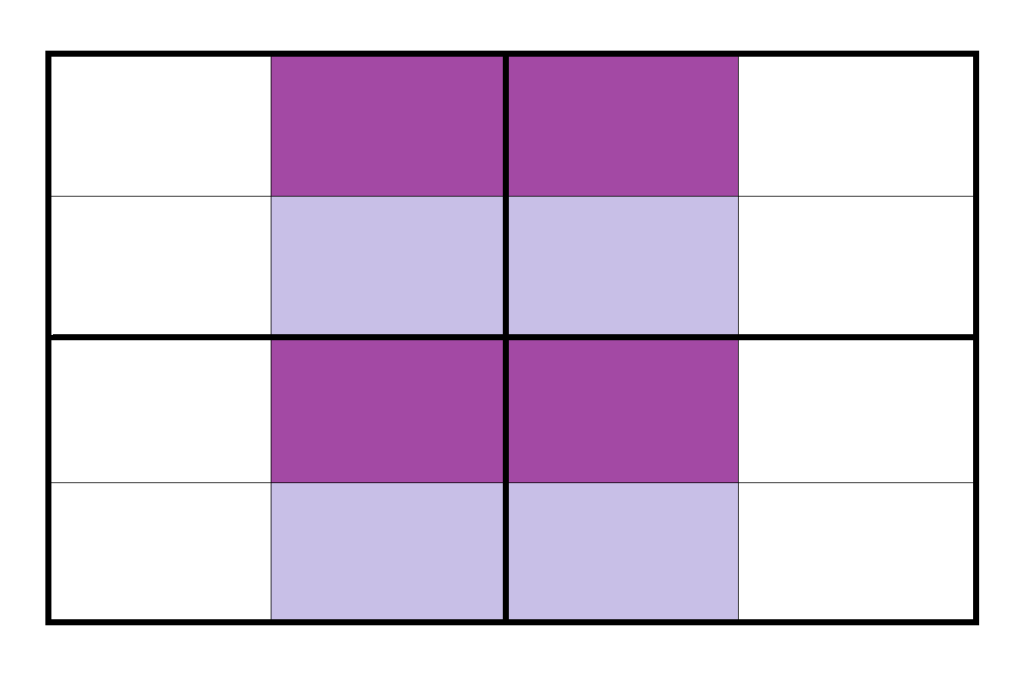

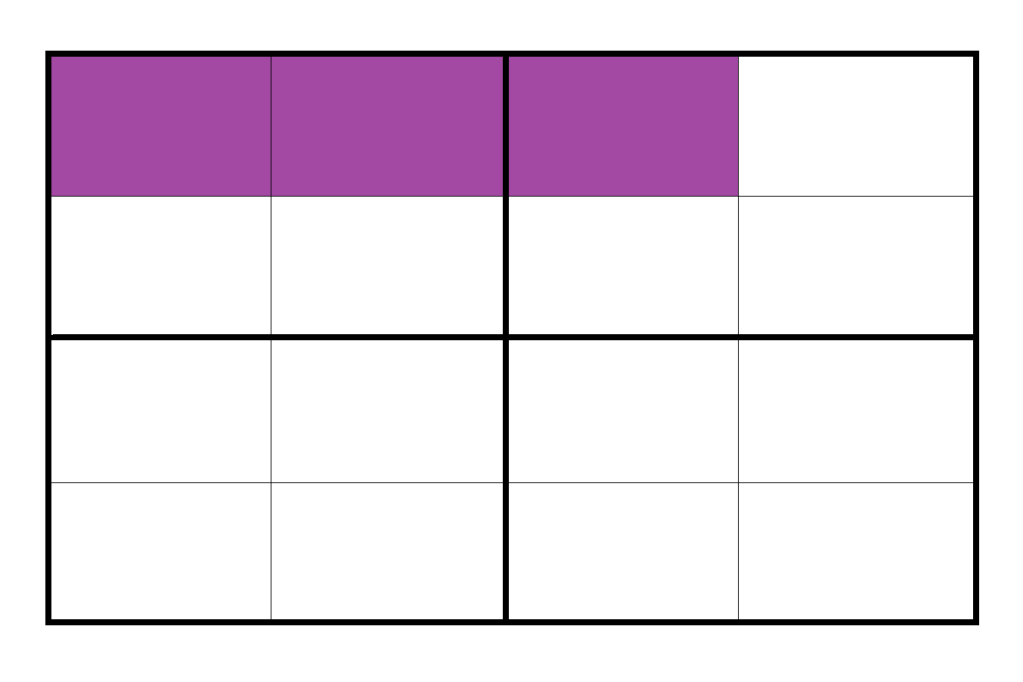

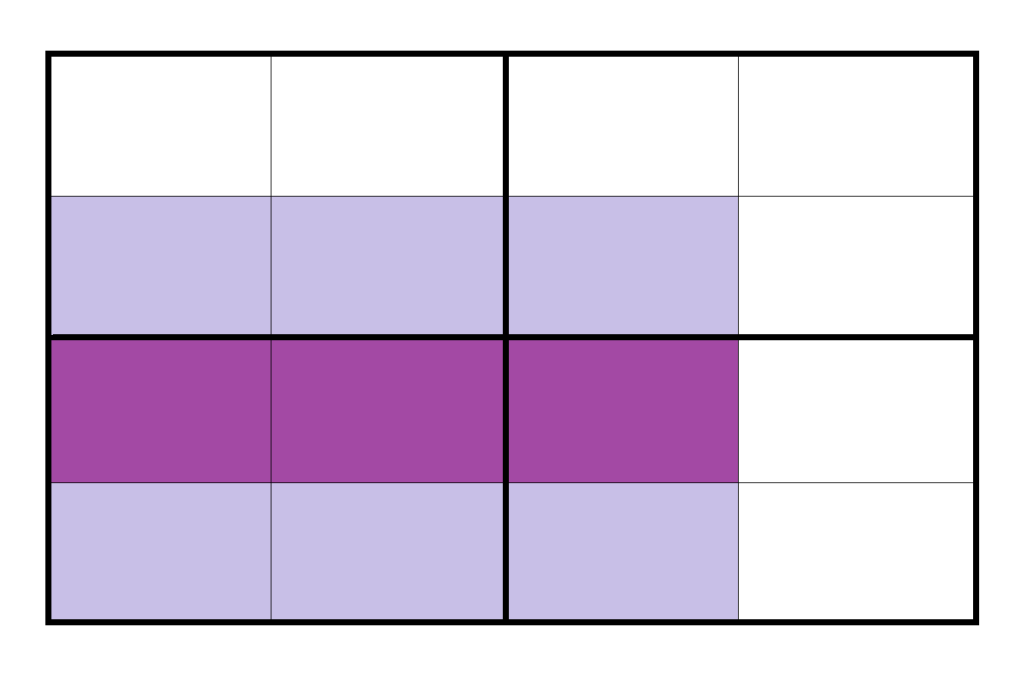

With these two major axes of change, now we can start to visualize what the care delivery landscape looks like in 2-dimensional space. Most CDO’s that provide core medical care can be segmented along both axes, and so every major type of CDO’s should a footprint (or multiple footprints) on this grid.

…with that said, here are the Archetypes (*in not particular order)

Smaller Community and Safety Net Hospitals:

Independently-run hospitals are the mainstay providers of secondary care, but they tend have limited capabilities in tertiary and quaternary care, and often lack the scale and resources to expand into alternative sites of care in the ancillary world. They also tend have a more limited footprint in the ambulatory world. These hospitals are commonly reliant on government support (DSH payments, or are directly run by local government) for solvency, and besides these supplementary payments, their economic model tend to be straight-forwardly fee for service.

Trend: waning, under threat – the economic model of these hospitals have always been tenuous, and now in light of the COVID crisis and increasing competition from larger systems, community hospitals face a tough road ahead.

National Community Hospital Systems (e.g. HCA, CHS, LifePoint, Tenet):

Like their smaller counterparts, these leviathan systems also tend to remain squarely in the FFS mode of doing business. These giants (often based out of greater Nashville), tend to be different from regional systems like Sutter or Northwell in that they are usually for-profit, and have a large multi-state geographic presence that is often not geographically contiguous. They also tend to run smaller community hospitals in rural or suburban areas, usually without strong academic ties. Some have expanded into ancillary sites like Urgent Care and Ambulatory Surgery, which tend to be profit-centers, as well as limited forays into virtual care.

Trend: stable – unlike their smaller brethren, these large systems are economically well in the black, and run very efficient ships. Their operational expertise and efficiency mean they are not under immediate threat, despite the fact that they are not moving with the times toward value-based economic models.

Large Regional Systems (e.g. Sutter, Advocate-Aurora, Northwell):

Regionally-dominant health systems have been expansionary in recent decades (e.g. the pending merger of Advocate-Aurora and Beaumont would create a Midwestern giant, and both Sutter and Northwell are the products of earlier mergers in the late 90s). Like academic systems, these systems have a broad footprint across different sites of care, from inpatient to outpatient and ancillary. However, compared to academics, regional systems tend to have a lighter footprint on the highly-acute quaternary end of the spectrum (cutting-edge experimental procedures still tend to take place in university-affiliated academic hospitals). These regional systems probably also have heavier footprints in ancillary services, especially in post-acute and long-term care. The economic models of these systems tend to remain mostly in the FFS world, with limited experiments in ACO’s and other risk-sharing arrangements.

Trend: stable/waxing – the trend of consolidation may very well continue and make bigger and more dominant regional systems, but with the increasing level of anti-trust scrutiny on recent deals, there is a finite roof to consolidation that we may be approaching.

Risk-Bearing Integrated Delivery Networks (IDN’s) (e.g. Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain, Geisinger, VA):

The economic model here is all the way to the right for Kaiser, which is a closed system that receives capitated payments for all its members. Intermountain and Geisinger, which takes FFS patients in addition to those on it’s own health plans, will land slightly more to the left. I would group the VA in this group as well, as the largest vertically-integrated healthcare system in the US. Site of care footprint is still for the most part centralized on inpatient care. These are still health systems whose architecture is centered on inpatient hospitals, although there are signs of change. However, since these organizations are huge comprehensive systems, they cover the spectrum of modes of care (all 4 segments by site of care), including outpatient clinics, physician groups, ancillary services like diagnostics/labs, OT/PT, alternative medicine, speech pathology, SNF’s hospice home health, and even telehealth.

Trend: stable – the big three here seem to be the only players in the non-government space that have executed this model at scale. They have done so successfully, and have strong and stable regional footprints. However, as some of Kaiser’s expansion efforts have shown, porting such a complex comprehensive model of care to new geographies is a daunting challenge, and I don’t believe this model will see rapid growth in the near future.

Traditional Academics (e.g. Northwestern Medicine):

University-affiliated academic medical centers (AMC’s) are regional health systems usually with flagship high-acuity quaternary care hospitals with strong academic affiliations and research and teaching missions. Many of these systems remain entrenched in the FFS way of doing business, especially since these hospitals tend to command high brand loyalty in its local markets, positioning it favorably in the FFS negotiation of rates with payers. These systems tend to also have a fairly broad site of care footprint, including large physician groups, and ancillary and virtual care assets as well.

Trend: stable – these AMC’s are well on the traditional side of the economic model spectrum, but given their strong market positions, they are not going anywhere.

Progressive AMC’s (e.g. Mt. Sinai):

Some academic systems are proactively moving towards a population health economic model, diversifying to include a significant value-based revenue stream. However, none of these systems are very far on this journey, and most of their business still retains a FFS structure. Large prominent systems like Mt. Sinai have both inpatient and outpatient assets, with a non-comprehensive set of ancillary assets (especially diagnostics and urgent care), and some virtual care assets as well like “Mount Sinai NOW Video Urgent Care,” but these services likely rely heavily on underlying vendor platforms.

Trend: waxing gradually – as first movers like Mt. Sinai pave the way and show its peers how an AMC might make the daunting transition to value-based care, other AMC’s will grow more likely to attempt a similar transition.

Specialty Hospitals (e.g. HSS, Cleveland Clinic Cardiology, MSK):

These hospitals focus on specific disciplines in a focused-factory model. They have a pretty exclusively inpatient footprint, but are more distributed in terms of economic model. Many are still well-entrenched in the FFS world, but others like Cleveland Clinic and Mayo Clinic (at least in certain service lines) are entering value-based arrangements like the Walmart centers of excellence program for their strongest specialties (Cardiology, and Orthopedics and Oncology and Transplant, respectively).

Trend: stable – specialty hospitals provide a specialized set of services that has few substitutes, while there is some experimentation with the economic model, they are an essential part of the ecosystem that has perhaps less of an impetus to change than others.

Retail-type Clinics and Urgent Care (e.g. CVS minute clinics, Concentra):

CVS is the biggest player with over 1,100 MinuteClinics. Other pharmacy chains like RiteAid and Walgreens have also been opening similar walk-in clinics within retail stores. Supermarket retailers like Walmart and Target have also be active in this space. These retail clinics tend to be staffed with advance practice providers like nurse practitioners or physician assistants, and the locations offer a limited set of outpatient services such as treating minor illnesses and injuries, vaccinations, and physicals. The economic model for most clinics are based on set prices for services, which are usually more competitive than equivalent services in a doctor’s office or hospital settings. Despite work-in-progress efforts to integrate these clinics into value-based care strategies, the core economic model here is mostly still a straightforward FFS model, albeit with greater price transparency. Urgent Care centers and Freestanding Emergency Rooms on the other hand, offer a wider set of services and can address higher acuity needs, but the economic model is also FFS. Collectively, the emergence of these new retail-type clinics have significantly expanded patient access and convenience to a core set of medical services.

Trend: waxing – this is a booming space, and it is taking advantage of the rising trend of consumerism within healthcare. The unit economics of the CVS and Walmart models have yet to be truly borne out, but in the meanwhile we will likely see more and more of these clinics, until they succeed or fail spectacularly when they prove to be ultimately profitable or not.

Independent Physicians (e.g. Hill Physicians, Healthcare Partners):

Excluding medical groups directly and exclusively affiliated with health systems (e.g. the Permanente Medical Groups) the remaining truly independent physicians are a bit of a dying breed. As more and more independent docs choose to join health systems, the number of small mom and pop practices, as well as the likes of behemoth groups like Hill Physicians are shrinking. Many of the remaining independent physician groups seem to be specialty groups, especially in lucrative specialties like orthopedics and ophthalmology which confers a financial incentive to remaining independent in order negotiate with payers and health systems from a position of strength. On the other hand, primary care practices like Hill Physicians and Healthcare Partners (now a part of OptumCare) continue to remain unaffiliated with hospitals, but these groups are shifting from a mixed value model of FFS practice with some “value-based” payment arrangements, to a heavier weighting of alternative payment models (resembling more and more primary care models that take on full risk). In terms of site of care, these groups by definition are primarily outpatient, but larger groups might have ancillary sites like urgent care, imaging centers, home care, and virtual care options.

Trend: waning – physicians have been migrating from independent practice to hospital-led systems for decades now, there is no indication of this trend reversing soon.

Community Health Centers (Federally-Qualified Health Centers, or FQHC’s) (e.g. Appalachian Mountain Community Health Centers, Erie Family Health Centers)

These non-profit, and sometimes faith-based chains of clinics tend to serve a population that is lower-income, and primarily covered by Medicaid or uninsured. These clinics are often the only option for healthcare for the populations they serve (other than the emergency room), and tend to be heavily reliant on government aid to supplement their FFS payments mostly from Medicaid. They emerged from the medical home concept, and trace their heritage to LBJ’s great society initiatives, under which these health centers were established by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity in mostly under-served inner city and rural areas. Today, they function primarily as outpatient clinics, but some have urgent care capabilities as well as ancillary services like pharmacies.

Trend: stable but tenuous – these centers are often the only resort for under-served populations, and as such play a critical role in our society. It is unlikely that the government will let them go anywhere, but nonetheless, they are chronically under-resourced and are not on the strongest financial grounds.

Medicare Advantage-focused Direct Primary Care (e.g. Oak Street, Iora, ChenMed, CareMore):

A new class of primary-care providers has taken the medical home concept and applied it in the Medicare Advantage market taking on full capitated risk. These companies tend to operate primarily or exclusively in Medicare Advantage, and they serve their patients through local clinics that also provide services like community activities, lifestyle/fitness activities, podiatry, etc… in addition to core primary care services. These organizations establish full-risk contracts with MA health plans, and several of them are in a similar point in their growth trajectory, currently operating around 50 clinics and rapidly expanding. In terms of site of care, these providers provide most of their services in-clinic, but also tend to have home health and virtual care capabilities, the latter of which has taken on the bulk of patient encounters during the COVID pandemic. Full disclosure, I will be starting work shortly at Oak Street Health, one of these companies that recently IPO’ed).

Trend: waxing – these startups have soundly demonstrated the profitable unit economics of this clinical model for elderly care, and a surge of investor interest and capital is fueling rapid growth and expansion.

Virtual Care (e.g. Amwell, Doctors on Demand, Zipnosis):

An emerging but still nascent class of providers are virtual care organizations. These companies which started to emerge mostly in the last decade, offers a wide variety of services (usually primary care) through synchronous and asynchronous digital solutions. Alongside retail clinics, this emerging trend has also helped to address the demand for more convenient patient access. Economic models vary, some players like Amwell offers most of its services in an episodic FFS fashion, while players like Doctor On Demand have developed a “digital medical home” product which bills itself as a smart platform that will “stitch together gaps in patients’ care and increase their overall access to healthcare services.” There are also instances of other healthcare companies with a different core business model venturing into this area, like Oscar Health, the NY-based digital insurance company which is expanding its footprint in care delivery with the upcoming launch of a virtual primary care program as a complementary service for its plan members in 10 of its markets.

Trend: waxing – The COVID pandemic may prove to be a watershed moment in the advent of virtual care at scale. The appetite and receptiveness to virtual care from both patients and providers has risen, and the promise of virtual primary care as a tool for care coordination has high potential appeal for a retail audience.

Final thoughts: These archetypes are obviously not exhaustive (ambulatory surgery chains, physical and occupational therapy clinics, inpatient psychiatric facilities, and many other CDO’s don’t appear), but in the spirit of brevity I tried to capture the major players that provide “core” medical services, especially primary, emergent, and inpatient care.

If we take a step back, and return to our 4×4 grid, it seems clear that the care delivery ecosystem is shifting down (towards alternative and peripheral sites of care) and to the right (toward alternative payment structures and value-based care). Change in healthcare however, as we know, is complicated, and the risks associated with breaking existing structures during transitions is deeply consequential, indeed potentially deadly. I have no doubt that the care delivery landscape of 2060 will be radically different from today, but given the immense challenge associated with transforming the way we care for the sick, it’s less clear how different the care ecosystem of 2030 or 2040 will be.